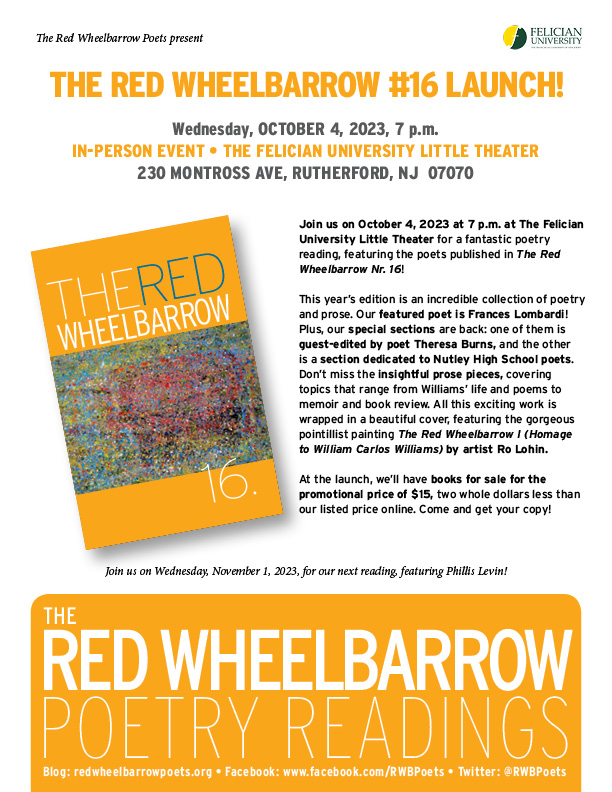

The Red Wheelbarrow (Volume 16) is open for submissions of poetry and essays from poets who have read their poetry as a featured poet or at the open mic at the monthly Red Wheelbarrow Poets reading series from July 7, 2022, through July 6, 2023. You are also invited to submit if you participated in any of the Red Wheelbarrow Poetry Workshops during the same period.

Please indicate in your cover letter when you’ve read with us or that you’ve attended the workshop to qualify. Simultaneous submissions are OK, but please notify us immediately if your work is accepted elsewhere.

When you submit, please complete the online form for one paragraph of relevant biographical information.

- Limit your bio paragraph to approximately 120 words.

- In the bio refer to yourself in the third person using your preferred pronoun (he, she, they).

We plan to publish and release Volume 16 in the fall of 2023.

PLEASE NOTE: THERE IS A SEPARATE DEADLINE FOR POETRY AND ESSAYS. ESSAYS ARE DUE MAY 1st. POETRY IS DUE JULY 4th.

Submission Guidelines for Essays

Please submit 1 (one) essay in a single Word document. The only acceptable file formats are .doc or .docx. No pdf or other file types will be accepted.

Format for the Submission Document

- Submit one Word document containing 1 (one) essay. Topics may include but not limited to: William Carlos Williams, New Jersey or Rutherford history, art, or poetry scenes, book reviews, writing craft. We’re pretty flexible.

- Maximum length: 2,500 words.

- Use Garamond, Times, or Times New Roman 12-point font.

- Do NOT use headers, footers, or automatic page numbering in the document.

- Do NOT use the footnote feature in Microsoft Word! If you want footnotes, do it manually.

- Your name should appear above the essay. Do NOT use All caps.

- If your submission relies on a special layout, please be aware of the print area this edition can allow: page printable area width is 4 3/4 inch by 6 3/4 inch length.

Submission deadline for essays: May 1, 2023. Click this Submittable link to submit.

Submission Guidelines for Poems

Please submit 5 (five) poems in a single Word document. The only acceptable file formats are .doc or .docx. No pdf or other file types will be accepted.

Format for the Submission Document

- Submit one Word document containing 5 (five) poems.

- Use Garamond, Times, or Times New Roman 12-point font.

- Do NOT use headers, footers, or automatic page numbering in the document.

- Do NOT use the footnote feature in Microsoft Word! If you want footnotes, do it manually.

- Your name should appear above the first poem. Do NOT use All caps.

- Each poem must have a page break at the end. Your poems should each start on a new page of the document.

- If your submission relies on a special layout, please be aware of the print area this edition can allow: page printable area width is 4 3/4 inch by 6 3/4 inch length.

Submission deadline for poems: July 4, 2023. Click this Submittable link to submit.

You must be logged in to post a comment.